Tags

Adolphe Crespin, Architecture, Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts Movement, Facade, Fresco, Heywood Sumner, Jugendstil, Paul Cauchie, Sgraffiti, Sgraffito

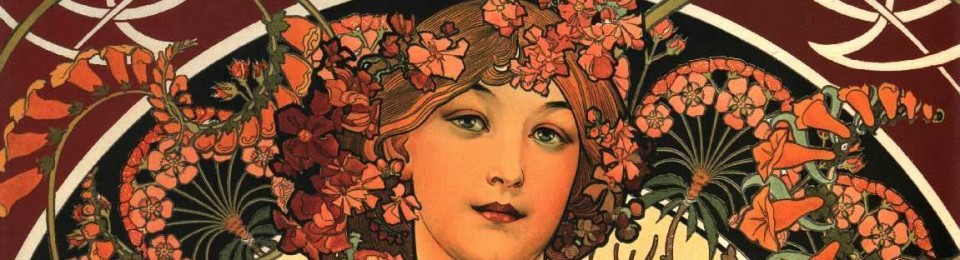

Hôtel Ciamberlani, designed by Ciamberlani & created by Crespin

In my search for the characteristics of Art Nouveau, I regularly stumbled upon big ‘façade-paintings’ like the one above, which I photographed in Brussels. What are they? How are they called and how are they produced? Are they a typical Art Nouveau thing? Somewhere, I read they are called Sgraffiti. But what are sgraffiti? I had never heard of them… it was about time to investigate the matter and find the answers!

What is Sgraffito?

I usually start by checking out what Wikipedia has to say about the subject:

Sgraffito (plural: sgraffiti; sometimes spelled scraffito) is a technique of wall decor, produced by applying layers of plaster tinted in contrasting colors to a moistened surface and then scratching so as to produce an outline drawing. Sgraffito comes from the Italian word graffiare “to scratch”, ultimately from the Greek γράφειν (gráphein) “to write”.

Sgraffito on walls has been used in Europe since classical times, it was common in Italy in the 16th century. But it can also be found in African art. In combination with ornamental decoration this technique formed an alternative to the prevailing painting of walls. The technical procedure is relatively simple, and similar to the painting of frescoes.

Examples of graphic work on facades saw a resurgence around 1890 through 1915, in the context of the rise of the Arts and Crafts Movement, the Vienna Secession, and particularly the Art Nouveau movement in Belgium and France.

The English artist Heywood Sumner has been identified as this era’s pioneer of the technique, for example his work at the 1892 St Mary’s Church, Sunbury, Surrey.

Belgian Sgraffito

According to JoostdeVree.nl (a well known Dutch source for architecture, engineering and other construction-related matters) there is a distinction though, between original or real sgraffito and Belgian sgraffito. In case of a real sgraffito, each color is a separate layer of plaster (tinted in a contrasting colour) applied to a moistened surface. Whereas the Belgian sgraffito consists of only one or two layers of plaster, in which the protruding lines or surfaces are painted ‘al fresco’ (on fresh plaster) or ‘al secco’ (on dry plaster). Belgian sgraffiti are often very colourful because the number of colours is not limited by the number of plaster layers.

1907, Privat Livemont, Rue Josaphat 229, Brussel

The famous Belgian decorator Adolphe Crespin pointed out that “a sgraffito is nothing more than a fresco emphasized by a line incised in depth. It concerns an engraving made in the mortar layer.” And that would confirm the distinction made by Joost de Vree.

Paul Cauchie

Probably the most popular sgraffito artist in Belgium was graphic-designer, painter and architect Paul Cauchie (1875-1952). Between 1894 and 1914, he applied more than 400 sgraffiti to façades. Paul married in 1905, and in that same year he decided to build a house on the six metre wide plot of land which he had bought at the upper end of the Rue des Francs. He designed the front of the house like a giant advertising billboard. It drew the attention of passers-by and demonstrated his abilities. This was done with the intention of advertising and selling his work. The Cauchie-house at Frankenstraat 5 in Brussels has been completely restored between 1980 and 1994, and is open for visitors. More information can be found here.

Sgraffito Fresco

From what I understand, the Italians also painted their plaster sometimes. They called this technique Sgraffito Fresco. A mix of the sgraffito technique ánd of fresco painting. Fresco painting means applying natural mineral pigments on a wet (fresco) plaster as soon as it has been prepared and laid on the wall. The colours can be absorbed by the wet plaster. When the plaster dries and hardens, the colours become one with plaster. (Technically speaking the plaster does not “dry” but rather a chemical reaction occurs in which calcium carbonate is formed as a result of carbon dioxide from the air combining with the calcium hydrate in the wet plaster.)

Façade of 134 rue Mouffetard, Paris (from 1929/1931 by Adigheri, Italian)

These Sgraffiti Fresco are not as colourful as the Belgian sgraffiti though. The technique became popular in Italy around the 15th or 16th century and was heavily used during the Renaissance period on the exterior of buildings. It has a typical two-tone execution and often covers the complete façade of a building. The themes were often virtual gardens, recovering natural elements that were lacking in the cities.

Sgraffito in Barcelona

Similar two-toned façades can be seen in Barcelona today. “The sgraffito technique took root in Catalonia back in the sixteenth century with the arrival of Italian master stuccoists. Two centuries later, this technique was experiencing a period of remarkable artistic splendour, based on ornamentations typical of Baroque and Neoclassical tastes. And while the technique practically fell into disuse during much of the nineteenth century, it was brought back into vogue in the early 20th century by the Modernista architects. It became a recurrent technique in facade decoration.” says Daniel Pifarré (dr. in History of Art, Barcelona). Take a look at my photo of the façade of Casa Amatller, to get an idea of such a spectacular façade.

1898, Casa Amatller, Barcelona

Why was Sgraffito só popular during the Art Nouveau Era?

So, besides Paul Cauchie, there were many more artists that made beautiful sgraffiti in Art Nouveau style, also outside Brussels. But why did this 16th century sgraffito-technique become such a typical Art Nouveau feature? What happened during the Art Nouveau era? Where did the ‘sgraffito-boom’ come from?

During the 19th century, the second industrial revolution more or less changed manufacturing methods. Little by little the work of craftsmen was replaced by the output of mass production. Prices dropped, goods became more accessible and the number of consumers rose sharply. The concept of the ‘department store’ was also invented, along with the first moves towards modern advertising. With the growth of the European population – which in 1900 made up a quarter of the world population – the birth of the consumer society was complete.

The structure of society was also affected by the industrial revolution. In this new industrial and urban world, the rural classes gave up their place in society and an immense working class emerged, along with a more prominent middle class. Society was now dominated by a bourgeoisie that had rapidly become wealthy. Powerful owners of the steel industry (known as the Masters of the Forge), railway or textile tycoons and pioneers of the car industry had a monopoly on power and influence which allowed them to indulge in their wealth. Completely new neighborhoods were built for the members of this bourgeoisie. And they gave particular attention to the maintenance and the decoration of their homes. Meanwhile the middle classes that sought to distinguish themselves from the working class, looked to imitate the opulent lifestyle of the bourgeoisie.

1905, Breestraat 65, Leiden

At the same time, artists and artisans started to resist mass-production. The Arts & Crafts Movement promoted craftsmanship, as was common in the late middle ages, before the modern world introduced machines. Such movements contributed to the resurgence of the decorative arts across Europe. Architects and decorators, encouraged by façades-competitions organised by the local authorities, rivalled in originality and mixed ornamental styles and techniques.

1900, Maison Beukman, Rue Faider 83, Brussel

Daniel Pifarré also mentions that “the fixation of Modernista architects on recovering former decorative techniques encouraged the resurgence of sgraffito as an ornamental solution on façades.” (I have put a link to Pifarré’s complete article on Catalan sgraffito at the end of this blog.) And let us not forget that each architect providing a space for the creation of sgraffiti (a ceiling, retaining wall, tympanum, frieze under the cornice…) created a dialogue between decoration and architecture which contributed to the creation of the so-called Total-Work-of-Art, or Gesamtkunstwerk, a popular concept during the Art Nouveau era.

And here comes the final clue: Even if there was no money for a complete new house in the latest fashion, one could easily incorporate small decorative details in the latest fashion in the design of a revamped façade. A door handle here, a boot scraper there, a colourful sgraffito… After all, adding a sgraffito was – compared to adding a new stone facade – relatively cheap and therefore also affordable for the not-so-extremely-rich.

1903, Singel 99, Dordrecht

It’s safe to conclude that the sgraffito is not a particular Art Nouveau invention, but an existing technique, a decorative feature from the Renaissance, that experienced a revival thanks to a wealthy bourgeoisie and the urge of the middle class to keep up with the Joneses.

Update: In 2023 a book was published about the Sgraffito of Barcelona.

Update: In 2023 a book was published about the Sgraffito of Barcelona.

Esgraffida Barcelona invites us to take a walk to discover the ‘skin’ of the city’s architecture and enjoy a rich heritage of borders, figures, floral motifs, garlands and advertisements that, tattooed on the façades, show the uniqueness and elegance of the buildings in the city. The book includes QR codes to locate the sgraffito buildings.

Continue Reading:

Architecture surfaces conservation: (re)discovering sgraffito in Portugal (PDF)

Barcelona – Esgrafiados (only pictures)

Columbia Heights- Sgraffito, Fresco Process

El paisaje urbano viste de esgrafiado

Een levensschets van Paul Cauchie, art-nouveaukunstenaar en kunstschilder (English summary) PDF

Façades Art Nouveau – Les Plus Beaux Sgraffites de Bruxelles

Joost de Vree – Bouwkunde – Sgraffito (Dutch)

La Barcelona esgrafiada, 1.500 obras de arte con el simple gesto de alzar la vista

Nasrid plasterwork: symbolism, materials & techniques V&A

Onderhoudsboekje Sgraffiti (PDF)

Repertoire des Sgraffites de_Liege (PDF)

Sgraffitokunst in Anderlecht, een wandelgids (PDF)

Sgraffito Techniek en Bescherming (PDF)

The Sgraffito of Heywood Sumner (1853–1940) (PDF)

The Success of Art Nouveau Sgraffito in Catalan Architecture (PDF)

Tur’Nouveau

What is Sgraffito Fresco? – introduction to history and facts

Gorgeous.

LikeLike

Pingback: Plateelbakkerij Holland, Utrecht (1894-1918) | Art Nouveau

Pingback: Breestraat 65, Leiden | Art Nouveau

Pingback: A Tour of Catalan Modernism in Barcelona - Forms of Beauty

Surprised there was no mention about the Catalan esgrafiat which is so prevalent and a major feature of much “Catalan modernist” architecture. Enjoy!

LikeLike

At the time when I wrote this post, I had not yet been to Barcelona. But you are right! Now that I have been to Barcelona twice, I understand what you are saying. It ís all-over-the-place in Barcelona. Maybe I should update my post and add this information. Thank you for your inspiration!

LikeLike